The following references the implementation of System.Collections.Generic.HashSet<T> in the .NET Framework 4.8, as it is shown here: https://referencesource.microsoft.com/#System.Core/System/Collections/Generic/HashSet.cs

The code below is simplified to show the ideas. No verification, exception handling, optimizations, etc. In other words: unsafe.

Please do not use in your project as is.

The best way to understand HashSet (in my opinion), is to ignore the hash part until the very end.

Leaving the question: What is a set?

Ignoring mathematical definitions, lets say a set is a way of grouping items without any specific order. The only property an item has in relation to a set is whether the set contains the item or not. Implicitly this prevents duplicates, since adding an item to a set that already contains it would not result in any new properties for either the set or the item.

For our code that means:

We need to be able to Add new items,

check if the set Contains a specific item,

and Remove an item from the set again.

All we need now to create our own set is a way to store those items.

Our first approach might be to repeat what we did for List. After all, List is designed to store data of (initially) unknown size. Same as our set, right?

Of course this would work, but where List leans more on the ‘add and keep data’ side, our set will have a lot of ‘add a bunch then remove some or all’.

And when removing a single item can result in tens of thousands of items needing to be moved in memory (true, i rarely have to work with that much data, but stay with me here), we might be better of finding a different storage structure.

Usually when needing memory we default to arrays (either directly or as the base for more complex types, like List), where items are simply placed in continuous blocks of memory. This makes it very easy to quickly access individual items, with the downside of requiring uninterrupted chunks of available free space.

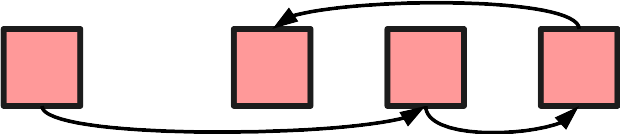

Alternatively there are linked lists. Here we store items inside small containers, which also store pointers to other containers. Access to specific items is tricky, since we need to iterate through the list until we find it. We also need a little extra memory to store the pointers (well, references, but close enough).

In return, we can fit the items anywhere in memory, making much more efficient use of free space. Better yet, we can easily change an existing list by changing some pointers instead of moving actual data.

Ideal for our set. Well, almost, but we’ll come to that.

For now, lets implement a simple Set using a linked list.

public class Set<T> { private class Item { internal readonly T Value; internal Item Next; internal Item(T value) { Value = value; Next = null; } } private Item _head; public Set() { _head = null; } public bool Add(T value) { Item prev = null; for (Item current = _head; !(current is null); prev = current, current = current.Next) if (Equals(current.Value, value)) return false; if (prev is null) _head = new Item(value); else prev.Next = new Item(value); return true; } public bool Contains(T value) { for (Item current = _head; !(current is null); current = current.Next) if (Equals(current.Value, value)) return true; return false; } public bool Remove(T value) { Item prev = null; for (Item current = _head; !(current is null); prev = current, current = current.Next) { if (!Equals(current.Value, value)) continue; if (prev is null) _head = _head.Next; else prev.Next = current.Next; return true; } return false; } }

And there it is.

A nested class Item to use as node in our linked list, and three methods to manipulate said list.

All of them return a boolean telling us whether or not the item was part of the set prior to executing the method.

Time to introduce a little twist: An array!

But why? After all, didn’t we use a linked list to avoid using arrays?

My best guess is performance.

I do not know the full reasoning behind this implementation in the official HashSet, but I can see the advantages it brings especially for memory (including the GC’s workload).

It is NOT needed for the hash part later. Not this array, at least.

But I digress.

Think back on the structure of a linked list. Now imagine that all those individual containers weren’t spread all over the memory, but arranged in a single line.

It is still a linked list. The order of items is determined by their references, not their position in memory.

Doesn’t this look just like an array?

Let’s start the implementation with an array to “reserve” a chunk of memory, in which we can place items for our linked list. This means that we can use indices inside that array instead of pointers. Which in turn makes it very easy to use a struct instead of a class for our nodes.

private struct Item { internal T Value; internal int Next; } private Item[] _items;

You can imagine _items to be a pool of Items, some in use, others free to take.

The challenge this presents us with is to manage this pool:

How do we find free items?

We could add a flag in Item, or use a big bit mask in Set.

Aside from the memory overhead those would add, they only tell us whether a specific item is in use. We still need to search the array for one.

There is however an easy solution that uses almost no extra memory and gives us quick access to the next free item:

A second linked list in the same array!

The basic idea is, that we have one list of items for our set, and one list of free items. All items in the array are always part of one of those two.

Whenever we add a value to the set, we take an item from the start of the free list.

Whenever we remove a value, we move it’s item back to the free list.

private int _head; private int _freeHead; public Set() { _items = new Item[10]; _head = -1; _freeHead = _items.Length - 1; for (int i = _freeHead; i >= 0; --i) _items[i].Next = i - 1; } public bool Add(T value) { int prev = -1; int current = _head; for (; current >= 0; prev = current, current = _items[current].Next) if (_items[current].Value.Equals(value)) return false; int added = _freeHead; _freeHead = _items[_freeHead].Next; if (prev < 0) _head = added; else _items[prev].Next = added; _items[added].Value = value; _items[added].Next = -1; return true; } public bool Contains(T value) { for (int current = _head; current >= 0; current = _items[current].Next) if (_items[current].Value.Equals(value)) return true; return false; } public bool Remove(T value) { int prev = -1; for (int current = _head; current >= 0; prev = current, current = _items[current].Next) { if (!_items[current].Value.Equals(value)) continue; if (prev < 0) _head = _items[current].Next; else _items[prev].Next = _items[current].Next; _items[current].Next = _freeHead; _freeHead = current; return true; } return false; }

This does work quite nicely.

Except for one crucial flaw: A constant size.

The Add method above assumes there will always be another free item.

But we initialize the array with a fixed length of 10…

What we need now is a similar function to what we have in List, to dynamically increase the size of our array when needed.

private void Grow() { Item[] newArray = new Item[GetNextLength()]; Array.Copy(_items, newArray, _items.Length); newArray[_items.Length].Next = _freeHead; _freeHead = newArray.Length - 1; for (int i = _freeHead; i > _items.Length; --i) newArray[i].Next = i - 1; _items = newArray; } public bool Add(T value) { int prev = -1; int current = _head; for (; current >= 0; prev = current, current = _items[current].Next) if (_items[current].Value.Equals(value)) return false; if (_freeHead < 0) Grow(); int added = _freeHead; _freeHead = _items[_freeHead].Next; if (prev < 0) _head = added; else _items[prev].Next = added; _items[added].Value = value; _items[added].Next = -1; return true; }

How does it grow, though? Double the size like List?

Not quite, HashSet is a little peculiar about this.

The new size it chooses is a prime number greater than or equal to double the current size, with an initial size of at least 3.

But not always the first prime. Up to a value of 7199639 primes are read from a static int array, which skips a lot of them. Any primes greater than that are calculated.

(We’re going to change those rules a bit and stick to the basic prime number idea).

To finish up the Set, let’s add a few details. These will pretty much mirror what HashSet does.

First, a counter to tell us the total amount of items.

We can simply use an internal integer to in- or decrement with every successful Add or Remove.

Secondly, we make a slight change to our “references”, by which i mean the indices of specific items in the array.

Instead of storing the actual index, we’ll store the index+1. So a reference to the second item is stored as 2, a reference to the first as 1 and a lack of any reference (what we used -1 for up to now) is stored as 0.

This is done to make the default value of Item.Next reference nothing, foregoing the need to change that value after initializing a new array.

This ties into our third change, in which we add an index for the lowest, untouched item in our array “pool”.

Essentially this allows us skip preparing the free items list.

When we need a free item, but the free list is empty, we can refer to the lowest untouched index.

Whenever we remove an item it is added to the free items list, to be used by the next add.

Basically we try to take up all the space in the lower part off the array first, moving into higher indices only when we run out of space.

Our Set now looks like this:

public class Set<T> { private struct Item { internal T Value; internal int Next; } private Item[] _items; private int _head; private int _freeHead; private int _lowestUntouchedIndex; private int _count; public int Count => _count; public Set() { _items = new Item[0]; _head = 0; _freeHead = 0; _lowestUntouchedIndex = 0; _count = 0; } public bool Add(T value) { int prev = 0; for (int current = _head; current > 0; prev = current, current = _items[current - 1].Next) if (_items[current - 1].Value.Equals(value)) return false; int added; if (_freeHead > 0) { added = _freeHead; _freeHead = _items[_freeHead - 1].Next; } else { if (_lowestUntouchedIndex >= _items.Length) Grow(); added = ++_lowestUntouchedIndex; } if (prev < 1) _head = added; else _items[prev - 1].Next = added; _items[added - 1].Value = value; _items[added - 1].Next = 0; ++_count; return true; } public bool Contains(T value) { for (int current = _head; current > 0; current = _items[current - 1].Next) if (_items[current - 1].Value.Equals(value)) return true; return false; } public bool Remove(T value) { int prev = 0; for (int current = _head; current > 0; prev = current, current = _items[current - 1].Next) { if (!_items[current - 1].Value.Equals(value)) continue; if (prev < 1) _head = _items[current - 1].Next; else _items[prev - 1].Next = _items[current - 1].Next; _items[current - 1].Next = _freeHead; _freeHead = current; --_count; return true; } return false; } private void Grow() { Item[] newArray = new Item[GetNextLength()]; Array.Copy(_items, newArray, _items.Length); _items = newArray; } private int GetNextLength() { int c = _items.Length * 2 + 1; for (; Enumerable.Range(2, (int)Math.Sqrt(c)).Any(d => c % d == 0); ++c) { } return c; } }

A fully functional, fairly optimized Set.

The largest performance sink is the time it takes to iterate through items to find a specific value. If only there was a way to….

Right, the hash part.

Finally here.

Let’s use an example:

Imagine a set that contains all integers from 1 to 100.

If we want to look for a specific value in this set, we’ll have to iterate through the entire linked list until we either find a match, or reach the end.

Best case: 1 iteration

Worst case: 100 iterations

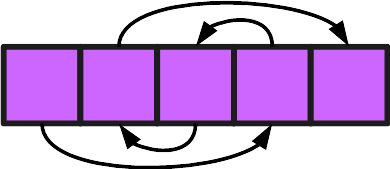

Now imagine our set being actually two sets (or more accurately, two linked lists in the same set):

One for values from 1 to 50, and one for 51 to 100.

Now whenever we want check for a value, we can simply choose which one to look in beforehand.

Best case: Still 1 iteration

Worst case: Now only 50 iterations

And why stop at two? Three sets? Ten? Why not one hundred?

The difficult part is the decision which set to use for a particular value.

An that is where we finally make use of a hash.

Every object in C# inherently allows us to use GetHashCode to generate an integer.

Objects with the same values always generate the same hash code, but different objects (ideally) generate different hash codes.

And how do we relate those to a specific linked list?

By using them as the index in an array of “pointers”.

Instead of a single field to store the head of a list, we now use an array to store several heads of as many lists as we like.

private int[] _mapping;

Using a simple modulo we can associate different hash codes with different positions in this array.

private int GetMappingIndex(T value) { int hashCode = value.GetHashCode(); if (hashCode < 0) hashCode = -hashCode; return hashCode % _mapping.Length; }

Keep in mind that hash codes might be negative. Here we simply invert the value if it is negative. Below we’ll do it like HashSet and clear the sign bit.

As a consequence of having the length of our array influence the calculated index, we have to redo the entire mapping every time our HashSet grows.

private void Grow() { Item[] newArray = new Item[GetNextLength()]; Array.Copy(_items, newArray, _items.Length); _items = newArray; _mapping = new int[_items.Length]; for (int i = 0; i < _lowestUntouchedIndex; ++i) { int mappedIndex = GetMappingIndex(_items[i].Value); _items[i].Next = _mapping[mappedIndex]; _mapping[mappedIndex] = i + 1; } }

Only one detail left before we’re done here.

In the code above, we’re calling GetHashCode again for items we’ve already processed, whenever the size changes. For complex objects this might be a non-trivial calculation and waste time.

Instead, items will store not only a value, but their hash as well, allowing us to simply reuse the stored hash, instead of regenerating it.

Since we already have the hash, we can also improve equality checks with it. Comparing two integers is an easy, quick operation. Not all comparisons are. If the hash of two objects is different, we don’t need to compare them to know they’re not equal.

public class HashSet<T> { private struct Item { internal T Value; internal int HashCode; internal int Next; } private Item[] _items; private int[] _mapping; private int _freeHead; private int _lowestUntouchedIndex; private int _count; public int Count => _count; public HashSet() { _items = new Item[3]; _mapping = new int[_items.Length]; _freeHead = 0; _lowestUntouchedIndex = 0; _count = 0; } public bool Add(T value) { if (Contains(value)) return false; int added; if (_freeHead > 0) { added = _freeHead; _freeHead = _items[_freeHead - 1].Next; } else { if (_lowestUntouchedIndex >= _items.Length) Grow(); added = ++_lowestUntouchedIndex; } (int index, int hashCode) = GetMappingIndex(value); _items[added - 1].Value = value; _items[added - 1].HashCode = hashCode; _items[added - 1].Next = _mapping[index]; _mapping[index] = added; ++_count; return true; } public bool Contains(T value) { (int index, int hashCode) = GetMappingIndex(value); for (int current = _mapping[index]; current > 0; current = _items[current - 1].Next) if (_items[current - 1].HashCode == hashCode && _items[current - 1].Value.Equals(value)) return true; return false; } public bool Remove(T value) { (int index, int hashCode) = GetMappingIndex(value); int prev = 0; for (int current = _mapping[index]; current > 0; prev = current, current = _items[current - 1].Next) { if (_items[current - 1].HashCode != hashCode || !_items[current - 1].Value.Equals(value)) continue; if (prev < 1) _mapping[index] = _items[current - 1].Next; else _items[prev - 1].Next = _items[current - 1].Next; _items[current - 1].Next = _freeHead; _freeHead = current; --_count; return true; } return false; } private (int Index, int HashCode) GetMappingIndex(T value) { int hashCode = value?.GetHashCode() ?? 0; hashCode &= 0x7FFFFFFF; int index = hashCode % _mapping.Length; return (index, hashCode); } private void Grow() { Item[] newArray = new Item[GetNextLength()]; Array.Copy(_items, newArray, _items.Length); _items = newArray; _mapping = new int[_items.Length]; for (int i = 0; i < _lowestUntouchedIndex; ++i) { int mappedIndex = _items[i].Next % _mapping.Length; _items[i].Next = _mapping[mappedIndex]; _mapping[mappedIndex] = i + 1; } } private int GetNextLength() { int c = _items.Length * 2 + 1; for (; Enumerable.Range(2, (int)Math.Sqrt(c)).Any(d => c % d == 0); ++c) { } return c; } }

And that’s it!

This is pretty much how HashSet works.

Well this and a lot of different methods to interact with the set, like intersections. But apart from some some fancy helper classes to handle bitmasks, i don’t think there is anything interesting for me to show you.

Most of the time it boils down to enumerating a bunch of items and performing one of the three basic operations with them.

My personal highlight is the linked list in an array.

Very confusing the first time i saw it.

But the idea has actually found a use in one of my projects recently, making it a nice companion to the “wrap object in struct” performance boost.