This is gonna be short…considering the scope of what I’ll attempt to write about.

Better read this in short bursts, with plenty of experimentation on your own.

Also: Brush up on XML. Nodes, attributes and how to escape characters. MSBuild is more or less a language written in XML – so you better know your way around it!

The big categories:

- Setup

- Targets

- Multiple Targets

- Properties

- Items

- Branching

- Tasks

- Custom Tasks

Let’s first introduce some metaphors to ease you into things (these are what i think of when working on build scripts):

Property

A string. A simple, singular text value.

Item

These are like arrays containing objects. Each object can have a set of properties different from the others.

Target

A (static) method. Each one can be called from other targets, chaining them.

Project

Class. Static though, just like targets. Contains targets and provides globally shared values.

Task

These are the commands that make up your “code”. There are a bunch of these predefined in MSBuild, but you can also create your own if needed.

You’ll want to play. A lot.

And for that you need a sandbox.

There are advantages to starting from an existing project in Visual Studio.

Not only does the IDE provide syntax highlighting and IntelliSense, the project comes bundled with a lot of existing “code” you can play with or learn from.

On the other hand, learning the basics might be easier with a clean plate.

So here’s my recommendation for you while getting used to MSBuild:

First, create a new (empty) file. The name doesn’t really matter, but it helps if the extension is .proj. I’ll call mine Dummy.proj.

Now open the file in Visual Studio (no Solution needed) and open a Terminal (View>Terminal), if you have none open.

In the terminal, use the cd command to move to the folder in which you’ve created the file before.

All we will be working with for a while are these two views: The open file and the terminal.

Try running the command msbuild.

If there are other project files in the folder you need to specify which one to build, e.g. msbuild Dummy.proj.

At this point you should get an error, telling you the root element is missing.

That means you did everything right and we can get to work!

Let’s start with a classic.

If this was C# we’d output the message with a simple command to the console.

That command needs a method to contain it.

Which itself has to be part of a class (ignore the namespace).

Before you comment on that, i am aware that in newer C# versions we can skip right to the command.

The same applies to our MSBuild version as well.

The root element of our XML is a Project, the counterpart of a static class:

<Project>

</Project>

Now we need a “method”, which we just add as a Target node to our project:

<Project>

<Target>

</Target>

</Project>

All nodes in MSBuild have attributes to further specify how the program behaves, some optional, some mandatory.

Target has one mandatory attribute: Its name. For now the name doesn’t matter, but once you start working on actual build processes you need to be careful (i’ll get into why later). To keep it in the spirit of our C# analogy let’s call it Main:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

</Target>

</Project>

And that’s already a valid MSBuild “program”. Just try the msbuild command in the terminal. The result should be a successful build.

To make anything happen during the build, we need to add “code” to our target in the form of at least one Task.

In this case that’s a task that outputs a message to the console: Message

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Hello, World!"/>

</Target>

</Project>

I think the task is easy enough to understand. Just call msbuild and let the magic happen!

Depending on where and how MSBuild is called you might not see the message. The default build output in Visual Studio for example will exclude messages of lesser importance.

Better get used to including Importance="high" in your Message calls!

What happens when we add a second target?

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Hello, World!"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Other">

<Message Text="Bye!"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Running this has the same result as before. But why?

Just like in most languages, we need a specific entry point.

If we don’t tell it which target fulfills that role, MSBuild will just take the very first one it finds.

Give it a try, switch the order of those two nodes and run it.

So how can we specify a target?

The first option is to specify a target with the attribute DefaultTargets in your project node:

<Project DefaultTargets="Other">

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Hello, World!"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Other">

<Message Text="Bye!"/>

</Target>

</Project>

As the name implies, you can actually give it more than one target, e.g. Other;Main . In that case they’re just run in that order. Give it try!

The more common way would be to specify the target in the msbuild call, using the argument -t, e.g. msbuild -t:Other.

Just like before you can give it several targets to run in order, though this time separated by , e.g. msbuild -t:Other,Main.

For the rest of this article my examples are run by calling Main using msbuild directly.

Assuming we only start with Main, how would we go about running Other as well?

The most direct approach would be to use the task CallTarget to call it.

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Hello, World!"/>

<CallTarget Targets="Other"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Other">

<Message Text="Bye!"/>

</Target>

</Project>

But the more interesting method is to add hooks to your targets.

For that purpose they have two attributes, BeforeTarget and AfterTarget. MSBuild will ensure that your targets are run according to your specification. For example:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Hello, World!"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Other" BeforeTargets="Main">

<Message Text="Bye!"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Will result in Other being run first, then Main.

Alternatively you can use the attribute DependsOnTargets to force another target to be run beforehand. Similar concept, but opposite control flow.

Remember what I said earlier about being careful with target names?

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Hello, World!"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Other" BeforeTargets="Main">

<Message Text="Bye!"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Other" BeforeTargets="Main">

<Message Text="Goodbye!"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Maybe to the surprise of some, this does indeed work without any issues.

What you will notice however, is that there is no “Bye!” written to the output.

That’s because MSBuild usually just overwrites elements of the same name.

You’ll see the same happening later with properties and items.

When the file is parsed, the first Other will get evaluated and stored, but is then completely overwritten by the second target of the same name.

Which is why you need to be careful with your names when working on larger build scripts with many already existing targets. Don’t shy away from large descriptive names!

One last tangent on targets before we get to the juicy bits.

What do you expect the output of this to look like:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Hello, World!"/>

<CallTarget Targets="Helper"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Other" AfterTargets="Main">

<Message Text="Bye!"/>

<CallTarget Targets="Helper"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Helper">

<Message Text="Helper is helpful..."/>

</Target>

</Project>

Did you try running it? Surprised?

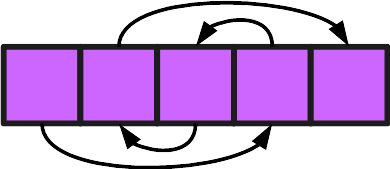

Targets in MSBuild are consumables. Each can be run only once per build.

It does make sense, in that each target has a specific purpose at a specific time during the build. Recurring tasks should be delegated to a (custom) Task, that can be called as often as needed.

Variables in MSBuild come in two different flavors, two datatypes if you will.

In both cases creating or modifying them requires a special node, which you can think of as declaring which type you’re using.

The easier to understand type is Property, and the special node we need is called PropertyGroup:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<PropertyGroup>

<Foo>Some string</Foo>

<Bar>42</Bar>

</PropertyGroup>

</Target>

</Project>

Here we created two “variables”.

One called Foo containing some text and one called Bar with text that happens to match a number.

Changing these values is done by overwriting them:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<PropertyGroup>

<Foo>Some string</Foo>

<Bar>42</Bar>

<Bar>21</Bar>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup>

<Foo>Some other string</Foo>

</PropertyGroup>

</Target>

</Project>

Which can be done in a different group or the same.

You probably want to see which values are stored inside those properties.

The syntax for that is $(<property>). Here are some examples of how you can use it:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Foo=$(Foo); Bar=$(Bar)"/>

<PropertyGroup>

<Foo>Some string</Foo>

<Bar>42</Bar>

</PropertyGroup>

<Message Text="Foo=$(Foo); Bar=$(Bar)"/>

<PropertyGroup>

<Foo>$(Foo) value</Foo>

<Bar>%24(Bar)</Bar>

</PropertyGroup>

<Message Text="Foo=$(Foo); Bar=$(Bar); %2524(Bar)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Points of note:

- Properties that aren’t defined yet can be used, they just don’t contain anything

- You can use existing properties when (re-)defining new ones

- “Escaping” is easiest with

%<ascii hex>

In the examples above we’ve just created properties inside a single target. You can however also define them outside of targets as part of the project:

<Project>

<PropertyGroup>

<Var>Some string</Var>

</PropertyGroup>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Var=$(Var)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

By the way, all definitions are evaluated before the first target is run, so it doesn’t matter where in the project you define them.

Meaning the above has the same result as this

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Var=$(Var)"/>

</Target>

<PropertyGroup>

<Var>Some string</Var>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>

and this

<Project>

<PropertyGroup>

<Var>No string</Var>

</PropertyGroup>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="Var=$(Var)"/>

</Target>

<PropertyGroup>

<Var>Some string</Var>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>

Let’s talk about scope.

If this were a C# program, we could expect the properties inside targets to be entirely local, and the ones defined outside to be shared between all targets.

MSBuild has different approach, which you probably best experience for yourself with plenty of experimentation.

For the less patient ones, here’s mental model:

- There is a global storage for all variables

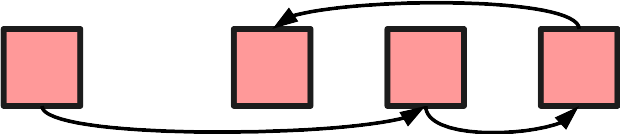

- Whenever a target is called, the then current global storage is cloned and used locally

- When a target finishes, it’s local storage is copied into the global one

<Project>

<PropertyGroup>

<Var>Global</Var>

</PropertyGroup>

<Target Name="Main">

<PropertyGroup>

<Var>Main</Var>

</PropertyGroup>

<CallTarget Targets="Foo"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Foo">

<Message Text="This is the global value: $(Var)"/>

</Target>

<Target Name="Bar" AfterTargets="Main">

<Message Text="This is from Main: $(Var)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Just like properties, items need to be defined inside a special node, an ItemGroup. And the same rules for their scope apply.

Otherwise items are a unique beast.

Their most prominent application is as a list of files, but you can easily make use of their features for other things.

To start of easy, let’s turn the file you’re working on into an item.

To do so we use the attribute Include, which you can pass one or more file paths into.

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<OurFile Include="Dummy.proj"/>

</ItemGroup>

</Target>

</Project>

The paths you enter are always relative to the file you ran MSBuild with.

And in my case its name is Dummy.proj.

There is another way to get the project file, one that works the same for me as it does for you:

MSBuild defines a few global properties itself whenever you run it.

One of those is MSBuildProjectFile, which stores the initial project file.

So this:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<OurFile Include="$(MSBuildProjectFile)"/>

</ItemGroup>

</Target>

</Project>

will put the file containing this very code into OurFile, no matter what name you chose.

Items in general are a list of different values, and each value is in of itself a set of key/value pairs. Which means we can’t just output the value in a message like we did with properties.

Well, technically we can, sort of.

The most basic approach would be almost identical to properties: @(<item>)

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<OurFile Include="$(MSBuildProjectFile)"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="@(OurFile)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Running this example doesn’t really show you the difference. And that’s alright for now, no need to rush.

Let’s focus on the key/value pairs i mentioned.

Each item has at least one of these. Some are predefined by MSBuild, others are custom additions you can make yourself.

To read those individually we include a format string in the item output:

@(<item>->'<format>') where format contains placeholders in the form of %(<key>).

The code above is basically the same as reading the Identity value:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<OurFile Include="$(MSBuildProjectFile)"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="@(OurFile->'%(Identity))')"/>

</Target>

</Project>

And of course the format string might contain other values as well:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<OurFile Include="$(MSBuildProjectFile)"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="@(OurFile->'%(Identity): %(RootDir)%(Directory)%(Filename)%(Extension) (Last changed on %(ModifiedTime))')"/>

</Target>

</Project>

These are some of the predefined values MSBuild provides.

To add our own, we need to modify the definition a little.

Imagine it as defining a property inside the item:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<OurFile Include="$(MSBuildProjectFile)">

<Foo>Bar</Foo>

</OurFile>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="@(OurFile->'%(Foo)')"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Just like with properties, you can use keys that aren’t defined for an item, they’ll just return an empty string.

For the next part I’m going to add a directory next the the project file, as well as two files in that directory:

Dummy.proj

Examples\A.txt

Examples\B.txt

When passing paths into the Include attribute, you can use wildcards to leave parts of the path unspecified. Effectively you get these options:

? for 1 character excluding the path separator

* for 0 or more characters excluding the path separator

** for 0 or more characters including the path separator

So this

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<TextFiles Include="Examples\*"/>

<AllFiles Include="**"/>

</ItemGroup>

</Target>

</Project>

will create two items. One contains only the files in “Example”, the other will also include the project file.

Which means we now have items that contain more than one value.

How do we display those?

By default all values in an item are chained together, separated by an ;.

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<TextFiles Include="Examples\*"/>

<AllFiles Include="**"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="@(TextFiles)"/>

<Message Text="@(AllFiles,' | ')"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Notice however what I did for AllFiles. Here i defined a custom separator for the output.

For some tasks, like in this case with Message, it’s fine to just list all values at once.

In many cases however, you want to perform actions for each value individually. For that we can make use of a similar syntax to what you saw earlier for formatting values:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<TextFiles Include="Examples\*"/>

<AllFiles Include="**"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="%(TextFiles.Identity)"/>

<Message Text="%(AllFiles.Filename): %(CreatedTime)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

This is called Batching, and it acts like a foreach loop that repeats a task for every value in an item.

You can generally use %(<key>), like in the format string, but somewhere you need to specify which item you’re referencing. Here that is done through %(<item>.<key>).

When you reference more than one item, the task is repeated once for all their values combined.

One of the interesting details about defining items is, that files you add to them with Include do not need to exist.

That means that this

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<Fictional Include="IdoNotExist"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="@(Fictional)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

will output “IdoNotExist” as if it were a real file.

Which also means that for the next parts we don’t have to rely on some existing files to experiment.

Unlike properties, you don’t overwrite items by creating a new definition.

Instead this will add the newly defined values to the existing list.

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<ABC Include="A"/>

<ABC Include="B"/>

<ABC Include="C"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="@(ABC)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Alternatively we could specify the values all in one go (something you can do for regular files with wildcards as well):

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<ABC Include="A;B;C"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="@(ABC)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Since the files are separated by ;, and the default output separates values by ; as well, we can do this:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<ABC Include="A;B;C"/>

<Clone Include="@(ABC)"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="ABC: @(ABC)"/>

<Message Text="Clone: @(Clone)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Now you might be wondering what this is used for.

If nothing else, it’s an excellent way of introducing the Exclude attribute.

Whatever you define in Exclude, is removed from whatever you define in Include.

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<ABC Include="A;B;C"/>

<Clone Include="@(ABC)" Exclude="C;D"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="ABC: @(ABC)"/>

<Message Text="Clone: @(Clone)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Of course if all you want is remove a value from your existing item you’re better of using the Remove attribute.

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<ABC Include="A;B;C"/>

<Clone Include="@(ABC)" Exclude="C;D"/>

<ABC Remove="C"/>

</ItemGroup>

<Message Text="ABC: @(ABC)"/>

<Message Text="Clone: @(Clone)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

So far we’ve got the ability to store values, both singular and in bulk, as well as a method for output and in a way even input.

What’s missing now, is a way to branch depending on our values.

That, and a way to repeat code. But that comes later.

Almost every node in MSBuild has the optional attribute Condition.

In those you can create logical statements that are either true or false.

If their condition evaluates to false, the entire node is ignored.

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<PropertyGroup>

<SomeValue>true</SomeValue>

</PropertyGroup>

<Message Condition="$(SomeValue)" Text="The value is true"/>

</Target>

</Project>

To chain together several conditions we have the classic operations (and brackets):

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<PropertyGroup>

<A>true</A>

<B>false</B>

</PropertyGroup>

<Message Condition="($(A) and !$(B)) or ( ! $(A) AND $(B) )" Text="A xor B is true"/>

<Message Condition="!( ($(A) AND !$(B)) oR (!$(A) aNd $(B)) )" Text="A xor B is false"/>

</Target>

</Project>

As you can see they’re case insensitive and you may add additional whitespace to increase readability if you want.

Since Condition can be used almost everywhere, we can also combine statements to reduce redundancy:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<PropertyGroup>

<A>false</A>

<B>false</B>

<Xor>false</Xor>

<Xor Condition="($(A) and !$(B)) or (!$(A) and $(B))">true</Xor>

<Nand>false</Nand>

</PropertyGroup>

<Message Text="A xor B = $(Xor)"/>

<PropertyGroup Condition="!($(A) and $(B))">

<Nand>true</Nand>

</PropertyGroup>

<Message Text="A nand B = $(Nand)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Besides simply chaining boolean values, we might want to compare values to create those booleans in the first place.

Again, the classics are all here:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<PropertyGroup>

<Int1>1</Int1>

<Int2>2</Int2>

<String1>ABC</String1>

</PropertyGroup>

<Message Condition="$(Int2)>=$(Int1)" Text="$(Int2)>=$(Int1)"/>

<Message Condition="$(Int1)<10" Text="$(Int1)<10"/>

<Message Condition="$(String1)!=$(String2)" Text="$(String1)!=$(String2)"/>

<Message Condition="'$(String1)'!='$(String2)'" Text="'$(String1)'!='$(String2)'"/>

<Message Condition="$(String1)=='ABC'" Text="$(String1)=='ABC'"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Of course there are other sources for getting booleans, and we’ll get to those in a bit. For the moment i just want to mention a very important one:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Condition="Exists('$(MSBuildProjectFile)')" Text="This file exists?!"/>

</Target>

</Project>

With Exists(<path>) you can check whether or not a file or directory actually exists. Very useful especially for working with items.

You probably picked up on it, but to clarify:

Values are interpreted based on context. Everything can be a text, but for boolean comparison that text needs to be true or false, and for value comparisons (except equality) the text needs to be a number.

I tried avoiding it so far, but at this point it doesn’t make sense not to link the Microsoft Docs:

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/visualstudio/msbuild/msbuild-task-reference

Essentially, tasks are all very specific, and highlighting each one and explaining their quirks would extend this already extended wall of text (which already exist elsewhere) even more.

That’s why I’m only showing one example before moving on to more custom code, using actual code.

That example is exec. This task allows you to run command line commands. Very useful to extend your builds capabilities, or for integrating existing batch scripts. The only mandatory parameter we need to provide is a command or program to execute.

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Exec Command="ROBOCOPY "D:\From" "D:\To" /e"/>

</Target>

</Project>

The command I’m running here is ROBOCOPY, to copy the entire data contained in D:\From to D:\To.

Unfortunately this build will fail quite often, even though the command is executed without any issues.

That is because exec fails if the command we’re running returns anything other than a 0. And ROBOCOPY has a lot of different exit codes even for successful executions.

That’s why we need to turn off the exit code evaluation with an optional parameter:

<Exec Command="ROBOCOPY "D:\From" "D:\To" /e" IgnoreExitCode="true"/>

Of course now we won’t know whether or not our data was copied successfully, and the build might fail at some other point because of it. Or even worse, the build might succeed, but the result is malformed.

What we need to do is evaluate the exit code ourselves, tailored to the specifics of our command. And to get the exit code we need to provide an output parameter:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Exec Command="ROBOCOPY "D:\From" "D:\To" /e" IgnoreExitCode="true">

<Output TaskParameter="ExitCode" PropertyName="OurExitCode"/>

</Exec>

<Error Condition="$(OurExitCode)>8" Text="ROBOCOPY failed: $(OurExitCode)"/>

<Message Text="ROBOCOPY succeeded"/>

</Target>

</Project>

If a task provides output parameters, you can nest Output nodes in it, to map them to a property or item of your choice. Here I mapped the parameter ExitCode to a property OurExitCode. This property is now created as if we defined it as part of a PropertyGroup.

Afterwards we can use the error task to fail the build, if the exit code indicates a problem.

As mentioned above, tasks are very specific. Just have a stroll through the Microsoft Docs to get an overview what you can do and what you can’t.

For whatever you don’t find, there’s always the option of creating it yourself.

To start off we’ll have a look at property functions.

The simple version are methods intrinsic to strings (as in, the .NET class string), which you can just call when “reading” a property:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<PropertyGroup>

<SomeText>ABC</SomeText>

</PropertyGroup>

<Message Text="$(SomeText.Substring(1))"/>

<Message Text="$(SomeText.Length)"/>

<Message Text="$(SomeText.Replace('B','D'))"/>

</Target>

</Project>

More complex is the second kind: Static method calls (and static properties).

The basic idea is to call a static method instead of reading a property, following the format $([Namespace.Class]::Method|Property).

So this outputs itself:

<Project>

<Target Name="Main">

<Message Text="$([System.IO.File]::ReadAllText('$(MSBuildProjectFile)'))"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Unfortunately there is only a limited number of classes that are available for this feature.

So what do you do when you need a task that doesn’t exist and can’t be replicated by a static call? You write your own task.

Custom Tasks can be included in a project by using a UsingTask.

Those allow you to import code as a DLL (if you want to compile it beforehand) or as source code directly (.cs or .vb files). And if you don’t want do deal with additional files to maintain, you can even write the code directly in your MSBuild file (my personal favorite).

To start of, let’s create a new .NET Framework Library, which I’ll call DummyTask.

And the first thing you should do afterwards is to add two references (you’ll find both in Assemblies):

Microsoft.Build.Utilities.Core

Microsoft.Build.Framework

Technically you only need the first to get things running, but you want the other, too.

All we need to do now is create a new (public) class that inherits from Microsoft.Build.Utilities.Task

and override its Execute() method. For now you can just have it return true.

using Microsoft.Build.Utilities;

namespace DummyTask

{

public class FooBar : Task

{

public override bool Execute()

{

return true;

}

}

}

And that’s it already on this end. A fully functional Task that doesn’t do anything.

In our MSBuild script we can import the Task with a single line:

<UsingTask TaskName="<Namespace>.<Class>" AssemblyFile="<PathToDLL>"/>

In my example that means something like this:

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="DummyTask.FooBar" AssemblyFile=".\DummyTask\bin\Debug\DummyTask.dll"/>

<Target Name="Main">

<FooBar/>

</Target>

</Project>

Running the target should simply succeed. No errors, warnings or output.

To change that, let’s add some output to see that everything worked. We can do so with a predefined method that mirrors the Message task:

using Microsoft.Build.Framework;

using Microsoft.Build.Utilities;

namespace DummyTask

{

public class FooBar : Task

{

public override bool Execute()

{

Log.LogMessage(MessageImportance.High, $"Message from {nameof(FooBar)}");

return true;

}

}

}

Running FooBar is now equivalent to running

<Message Importance="high" Text="Message from FooBar"/>

This kind of task might have its uses, e.g. as a heartbeat to let you know the Buildserver hasn’t crashed, the build just takes longer. But for the most part you want the task to read from and/or write to Items and Properties.

The necessary code is is surprisingly simple. All we need to do is add a property to our class:

using Microsoft.Build.Framework;

using Microsoft.Build.Utilities;

namespace DummyTask

{

public class FooBar : Task

{

public string SomeValue { get; set; }

public override bool Execute()

{

Log.LogMessage(MessageImportance.High, $"The value is: {SomeValue ?? "NULL"}");

return true;

}

}

}

With that we have a simple input for our task:

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="DummyTask.FooBar" AssemblyFile=".\DummyTask\bin\Debug\DummyTask.dll"/>

<Target Name="Main">

<FooBar/>

<FooBar SomeValue=""/>

<FooBar SomeValue="abc"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Note how our property receives a default value if not given a value, meaning we have to deal with null.

Unless of course we use a different data type. The property can be any IConvertible, which means this works as well:

public int SomeValue { get; set; }

<FooBar/>

<FooBar SomeValue=""/>

<FooBar SomeValue="1"/>

If you don’t want to deal with default values, you can mark a property as mandatory with the Required attribute.

[Required]

public string SomeValue { get; set; }

Now the build will fail if no value is provided.

That value was a simple property so far. What about items?

For those we need the data type ITaskItem, which essentially is collection of Key/Value pairs.

using Microsoft.Build.Framework;

using Microsoft.Build.Utilities;

namespace DummyTask

{

public class FooBar : Task

{

public ITaskItem SomeValue { get; set; }

public override bool Execute()

{

Log.LogMessage(MessageImportance.High, $"The item is: {SomeValue.ItemSpec}");

foreach (string property in SomeValue.MetadataNames)

{

Log.LogMessage(MessageImportance.High, $"{property}: {SomeValue.GetMetadata(property)}");

}

return true;

}

}

}

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="DummyTask.FooBar" AssemblyFile=".\DummyTask\bin\Debug\DummyTask.dll"/>

<Target Name="Main">

<ItemGroup>

<Example Include="$(MSBuildProjectFile)">

<CustomProperty>CP Value</CustomProperty>

</Example>

</ItemGroup>

<FooBar SomeValue="@(Example)"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Of course items usually come as part of a list, so our property should accept more than one:

public ITaskItem[] SomeValue { get; set; }

What if your task should output values? You simply mark the property as Output.

[Output]

public string SomeValue { get; set; }

public override bool Execute()

{

SomeValue = $@"{Environment.UserDomainName}\{Environment.UserName}";

return true;

}

<FooBar>

<Output TaskParameter="SomeValue" PropertyName="CurrentUser"/>

</FooBar>

<Message Text="Current user: $(CurrentUser)"/>

And finally (if that wasn’t obvious by now): The return value of Execute is evaluated by MSBuild to decide if the build failed or may continue. You can always log error messages, but they don’t determine whether or not the build actually failed.

That’s it already. Pretty simple, right?

The most complicated part is setting up the project and adding the DLL to your build script.

I compiled the code as a .NET Framework library, but you can also use .NET Standard.

Both are accepted by UsingTask.

Going a step further, we can put the source code of our task inside the MSBuild script to have it be compiled and run automatically, without us doing anything.

Before, we used the TaskName and AssemblyFile attributes of the UsingTask to specifiy a specific class in our compiled DLL file.

Now we’re going to use TaskName to define the name, and AssemblyFile to reference a library that can compile our code. Luckily MSBuild already offers one such library, meaning we can do this (ignore that the build would fail):

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="FooBar" AssemblyFile="$(MSBuildToolsPath)\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.Core.dll" TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory"/>

<Target Name="Main">

<FooBar/>

</Target>

</Project>

Providing a library isn’t enough though. We also need to specify which part of it to use, by providing a value for TaskFactory. Use CodeTaskFactory if you’re writing .NET Framework code and RoslynCodeTaskFactory for .NET Standard.

As you’ll quickly find out when running the above script, we’re missing some parts now.

First, we need to specify the “signature” of our task, meaning its attributes and what output it provides. Our first task will have neither, so we can skip this for now.

Next is the actual code, which can be the entire class we wrote before, only the Execute method or even just its body. So this will already work:

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="FooBar" TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory" AssemblyFile="$(MSBuildToolsPath)\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.Core.dll">

<Task>

<Code>

Log.LogMessage("FooBar!");

</Code>

</Task>

</UsingTask>

<Target Name="Main">

<FooBar/>

</Target>

</Project>

The code factory will use that data and generate some code for it before compiling:

//------------------------------------------------------------------------------

// <auto-generated>

// This code was generated by a tool.

// Runtime Version:4.0.30319.42000

//

// Changes to this file may cause incorrect behavior and will be lost if

// the code is regenerated.

// </auto-generated>

//------------------------------------------------------------------------------

namespace InlineCode

{

using System;

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Text;

using System.Linq;

using System.IO;

using Microsoft.Build.Framework;

using Microsoft.Build.Utilities;

public class FooBar : Microsoft.Build.Utilities.Task

{

private bool _Success = true;

public virtual bool Success

{

get

{

return _Success;

}

set

{

_Success = value;

}

}

public override bool Execute()

{

Log.LogMessage("FooBar!");

return _Success;

}

}

}

And yes, that means you can use the Success property to signal a failure in your task as an alternative to the return statement.

Since we have no project, certain settings need to be provided by XML. Those being using statements you would make in your code files, and DLL references in the project file.

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="FooBar" TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory" AssemblyFile="$(MSBuildToolsPath)\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.Core.dll">

<Task>

<Reference Include="System.Windows.Forms"/>

<Using Namespace="System.Windows.Forms"/>

<Code>

MessageBox.Show("FooBar!", "$(MSBuildProjectFile)");

</Code>

</Task>

</UsingTask>

<Target Name="Main">

<FooBar/>

</Target>

</Project>

To define our “signature”, we just add parameters as part of a ParameterGroup, where we can also specify additional attributes to determine how they are used.

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="FooBar" TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory" AssemblyFile="$(MSBuildToolsPath)\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.Core.dll">

<ParameterGroup>

<Desc/>

<Values Required="true" ParameterType="System.Int32[]"/>

<Sum Output="true"/>

</ParameterGroup>

<Task>

<Code>

Sum=Values.Sum().ToString();

if(Desc!=null)

Sum=string.Format(Desc,Sum);

</Code>

</Task>

</UsingTask>

<Target Name="Main">

<FooBar Values="1;2;3;4;5;6" Desc="Sum of digits on a D6 is {0}">

<Output TaskParameter="Sum" PropertyName="Sum"/>

</FooBar>

<Message Text="$(Sum)" Importance="high"/>

</Target>

</Project>

If you need more control over the code, you can choose how much you provide and what is added by the CodeTaskFactory with the attrtibute Type in Code. Your options are:

Fragment – Method body of Execute

Method – The entire method Execute

Class – The entire code file

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="FooBar" TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory" AssemblyFile="$(MSBuildToolsPath)\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.Core.dll">

<ParameterGroup>

<Desc/>

<Values Required="true" ParameterType="System.Int32[]"/>

<Sum Output="true"/>

</ParameterGroup>

<Task>

<Code Type="Class">

using System.Linq;

using Microsoft.Build.Framework;

using Microsoft.Build.Utilities;

namespace DummyTask

{

public class Summarizer

{

public int Sum { get; set; }

public string Desc { get; set; }

public override string ToString()

{

if (Desc == null)

return Sum.ToString();

return string.Format(Desc, Sum);

}

}

public class FooBar : Task

{

public string Desc { get; set; }

[Required]

public int[] Values { get; set; }

[Output]

public string Sum { get; set; }

public override bool Execute()

{

Summarizer summarizer = new Summarizer

{

Sum = Values.Sum(),

Desc = Desc

};

Sum = summarizer.ToString();

return true;

}

}

}

</Code>

</Task>

</UsingTask>

<Target Name="Main">

<FooBar Values="1;2;3;4;5;6" Desc="Sum of digits on a D6 is {0}">

<Output TaskParameter="Sum" PropertyName="Sum"/>

</FooBar>

<Message Text="$(Sum)" Importance="high"/>

</Target>

</Project>

If your code really requires this much control, you might be better off storing it separately in its own file. You then can reference it in Code using the Source attribute. Though of course at that point you might be better off switching to a DLL instead.

Also important to keep in mind: Your code is simply text data inside an XML node. You will have to escape some common characters like <, > and &.

Or you can escape the entire code in a CDATA block:

<Project>

<UsingTask TaskName="Range" TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory" AssemblyFile="$(MSBuildToolsPath)\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.Core.dll">

<ParameterGroup>

<Limit Required="true" ParameterType="System.Int32"/>

<List Output="true" ParameterType="Microsoft.Build.Framework.ITaskItem[]"/>

</ParameterGroup>

<Task>

<Code>

<![CDATA[

if (Limit > 1000)

Log.LogError("Limit must be 1000 or less");

else if (Limit < 1)

Log.LogError("Limit must be 1 or greater");

Success = false;

if (Limit >= 0 && Limit <= 1000)

{

Success = true;

List = new ITaskItem[Limit+1];

for (int i = 0; i <= Limit; ++i)

List[i] = new TaskItem(i.ToString());

}

]]>

</Code>

</Task>

</UsingTask>

<Target Name="Main">

<Range Limit="10">

<Output TaskParameter="List" ItemName="Range"/>

</Range>

<Message Text="@(Range)" Importance="high"/>

</Target>

</Project>

Yes.

No? I feel like i have both written too much and too little at the same time.

Honestly, all i wanted to provide is a collection of all the things i had to teach myself in order to upgrade my build game. But….it’s not enough.

MSBuild is huge. There are so many details i never use and therefore didn’t cover, and many more i don’t even know about.

Your best bet is to play around and search the net.

A little warning: Visual Studio doesn’t always play nice with your edits to its projects. Instead, try to put your changes into separate files you can import.